Hammered

Why making is crucial to my writing.

The mission I have with my books, is to light a spark of curiosity about how the human-made world around us works. Someone recently asked me if being an engineer changes the way I see the world. It does, so much. To the extent that a long-running complaint from my husband is that our holiday pictures are 99% bricks, arches and cantilevers, and 1% him.

To convey how the objects I write about are created is important — it gives the reader a sense of making, moulding, and materials. It brings the black & white page to life. It reveals a small world which you may or may not have encountered first hand. And to do this well, I need to have a go myself.

It’s really nothing to do with me wanting to make stuff and have fun. It’s serious research. Promise.

So this month, I will share what it’s like to forge a nail. I was expertly guided by blacksmith and educator Rich Maynard (hi Rich!) in a forge in Much Hadham, a forge which has been running continuously since the late 19th century.

Enjoy. And please share, in the comments, your experiences of making something new!

As always, it really means a lot to me if you can hit like, or share this post or my newsletter with friends and family. Surely they want to know more about nail-making…

*excerpt from the first chapter of Nuts & Bolts.

‘Red-hot? Not hot enough,’ yelled Rich over the din of the workshop.

With my bare hands, I’ve been gingerly holding on to the top of a thin steel rod about the length of my arm. The bottom is submerged in coke burning in a brick furnace at over 1,000°C. An electric fan blows air on the flame to make it even hotter. But when I pull the rod out to check its colour, which is an angry glowing red, Rich, the blacksmith, tells me it’s not ready yet. So I shove it back into the fire until it brightens to a searing orangey-yellow. Now, with this luminous piece of steel, I can get to work on making a nail.

For this, I need tools. Before me is an anvil – the classic hulking iron blacksmith’s block – with the legend ‘102 kgs’ stamped on its side.

Angling the rod so its glowing end rests on the flat surface of the anvil, I hit the end with a heavy hammer, and the metal flattens a little. I hit it a few more times, then rotate the rod by ninety degrees, and hit it again. After a while, though, the end of the rod darkens; I can feel the hammer bounce, and the sound of the clanging becomes sharper. The rod has cooled. So back in the fire it goes until it reaches orangey-yellowness again. Hammer, rotate, reheat. It takes me three cycles of this to fashion a fairly good taper at the end of the rod. (Rich can do it in one.) But finally, I have the body of my nail.

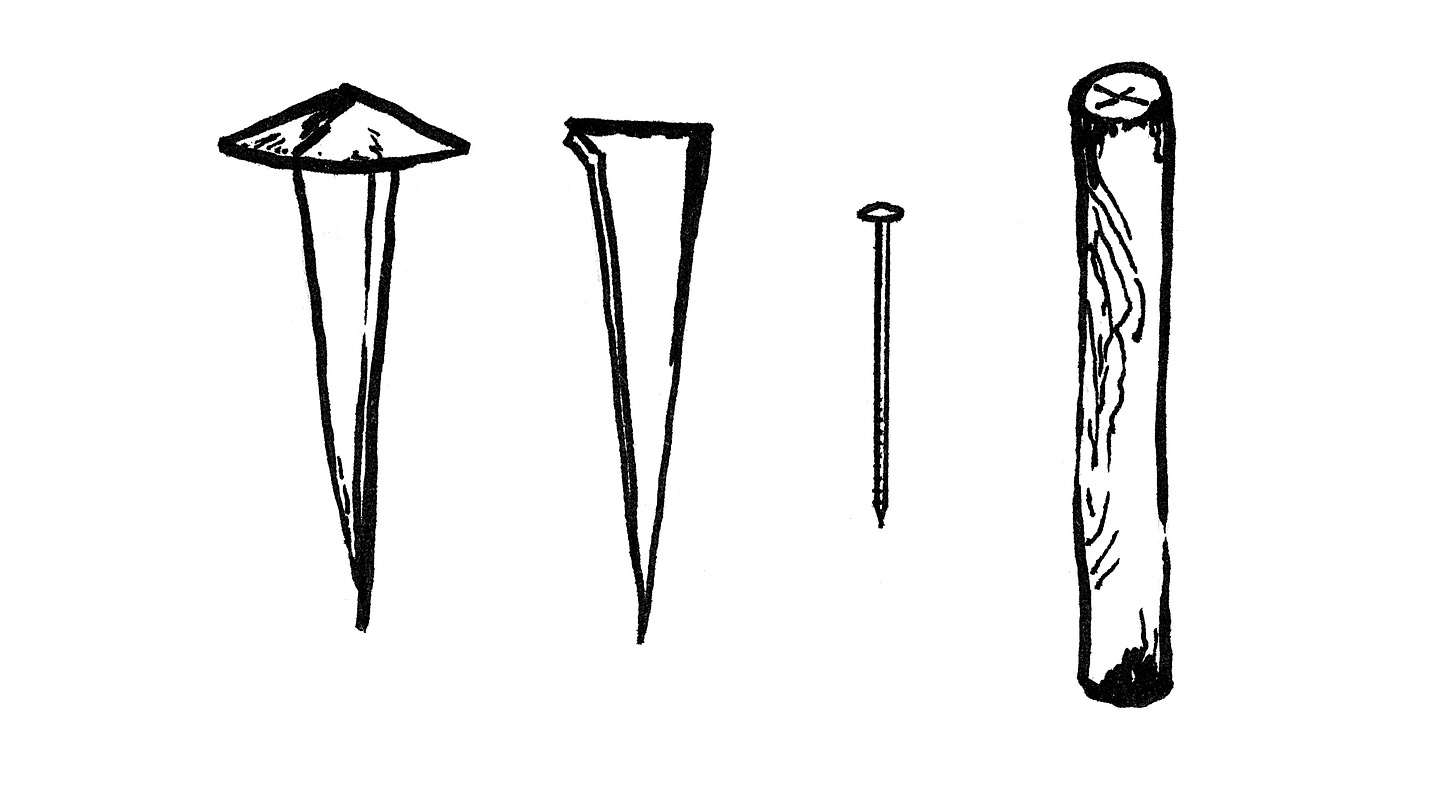

Next, I slot a chisel – sharp end pointing up – into a square hole in the anvil known as the ‘hardy hole.’ I lay my reheated, tapered rod across the chisel blade and hit it hard (as hard as nails, perhaps) to notch two sides, which will make it easier to separate the tapered end from the rest of the rod. The last tool I need is the heading tool: a long, rectangular metal plate studded with different-sized holes, as though it’s been attacked by a hole-punch. Choosing a hole that is large enough to allow most of the taper through, I insert my nail-to-be. With some strenuous twisting, I break the rest of the rod away from the nail. Now the point of the nail hangs down through the hole, with about a centimetre of head poking through the top. After lining up the point of the nail with a circular hole on the anvil, I quickly bash the top to flatten it and create the nail head.

Finally, the ‘quenching’: I plunge the whole plate and nail into a trough of water, producing a satisfying sizzle and clouds of steam as hot hits cold. I pull them out, give a gentle tap with the hammer to release the nail from the heading tool, and it falls to the floor with a clang. My humble, and still slightly warm, creation.

Nails may seem like a simple piece of engineering, but take a look around you, and you’ll see that they are everywhere. From my desk, as I write, I can see pictures suspended from them and bookshelves fixed together with them. The desk itself is secured with them, as are the shoes I’ve just kicked off underneath. The walls, made from panels of wood underneath the plaster, and the floor, resting on wooden joists, are all joined with nails. Most of these nails I can’t actually see, because their bodies are buried in wood, leather, and brick, but I’m aware of their silent, reassuring presence.

Reading this chapter, I definitely thought of my own experiences in a blacksmithing shop. It is such hard work! I found it very satisfying to transform the square bar stock into a twisted curlicue and then plunge it into the quench. It’s definitely a very physically demanding craft.

Hi Roma!